Zen: A New Approach to Authoring the Web

Web-Page Editing and Web App Development Based upon Direct Manipulation of the DOM and Visual ProgrammingVersion 0.11.10

by Tom Elam

Elam & Associates

Mysuru, India

January 6, 2020

1. Introduction

This white paper presents a profoundly unique, personalized, and adaptive approach to the creation of web experiences—a radically new approach usable by a very broad class of people. It links to live prototypes of web-page-editor interfaces to demonstrate that it could be possible for end users to build their own web pages from scratch and decide every detail of their web pages' look and structure simply, easily, and quickly, without any prior learning. The possibilities go far beyond just editing web pages, which this paper also intends to show. The code name for this approach and its implementation (under development) is Zen. The unique selling point (USP) of Zen will be in-context, instant-feedback, full-featured editing of website or web app structure, function, and styling. In particular, Zen will make it easy for users to create any kind of valid HTML structure in web pages without getting into the complexity or distraction of code and will make it easy for them to create basic-level programs using visual-programming principles adopted from successful visual-programming languages for children. Most importantly, all this "development" and its deployment can be continuous, carried on by a website's users of all levels of experience. Since, with Zen, deploying and sharing a new application could be as simple as clicking a Share or Deploy button, self-organizing user communities might develop altogether novel applications.

A deliverable of the Zen project will be an example Zen-based web application framework1 comprising the Zen client-side JavaScript library, aka Core Zen, and a liberally licensed server-side framework (possibly Ruby on Rails) augmented with code to store and serve the web pages created and modified by Zen. Even though Core Zen will only have to be loaded once to create an unlimited number of web pages with unique URLs, a strong effort will be made to keep the "time-to-interact" (TTI) delay introduced by Core Zen down to 2–3 seconds, so that Zen's potential application can be as broad as possible. (TTI is the time it takes from the start of a web page load until the time when the user is comfortable interacting with the web page.) Potentially many other implementations of Zen could be developed to incorporate and integrate Core Zen into web content management systems, wikis, website builders, web frameworks, web portals, web development tools for editing, testing, and debugging code, and integrated development environments (IDEs) for web development. Web services such as Google's Accelerated Mobile Pages (AMP)2 and Google Hosted Libraries3 could broaden Zen's potential.

Many user-programmed systems for customizing websites are described in the book No Code Required: Giving Users Tools to Transform the Web 4 but no system for creating web apps. With Zen, many kinds of web apps will be created as simply as are the applications written by children in specially designed visual programming languages. (Specific references to these child-oriented systems are provided later in this paper.)

Though many of the problems of creating end-user programming environments have been overcome to some degree or other, there is one obstacle to it that still has no embeddable (library-based) solution—as opposed to a framework-based solution. That is a problem that arises from the stateless nature of the Web. To illustrate, we take an example of a typical program that asks a user's name and greets him accordingly:

PRINT "What is your name?"

INPUT "(Enter your name.)", $name

PRINT

PRINT "Hello, "; $name; ", how are you today?"

The flow of this program is obvious, but even such a simple program must be written on

a platform that hides complexity:

it must be halted, waiting for a response.

This is true no matter what the programming platform is.

For desktop applications, the operating system provides system calls, a scheduler,

and library functions that

allow program flow to mirror the thread or process of the program, as in the example.

For web apps there is no underlying operating system to support the halting and restarting

of the program.

However, some languages, such as Scheme, support continuations,5

which allow programs written in that language to be halted and restarted using

language-level mechanisms (as opposed to operating-styem system calls and library functions).

Zen will utilize continuations to simplify the end-user's programming tasks.

Why Zen's new approach is desirable and how it is anticipated to work are the subjects of this whole paper, but a brief video from the Digital Archaeology project1 showing the operation of the first web browser can provide some background context. The video shows the operation of the first web browser, called Nexus, crafted by the inventor of the World Wide Web himself, Sir Tim Berners-Lee. Twelve minutes and nine seconds into the video, Nexus's editing function is demonstrated (Figure 1). Thus, from the very beginning, Berners-Lee intended the web browser to enable easy collaborative authoring. However, as he himself says, "It didn't really take off that way."2, 3, 4

Now, a quarter of a century later, the position of the A-grade web browsers5, 6, 7, 8 as the central applications for online sharing seems unshakeable. Yet till today, not one A-grade web browser has full-fledged web-authoring capabilities. (We shall discuss the browser features contentEditable and designMode later, since these do not, without external programming, constitute web-authoring capabilities.) The direct descendents of Berners-Lee's early web-page editing application are visual web-page editors in three broad categories:

- In-browser rich-text editors. These are web-page-embedded, JavaScript-based, WYSIWYG web-page editors that convert HTML textarea fields or other HTML elements into editor instances. TinyMCE and CKeditor are typical examples.

- Standalone WYSIWYG web-page editors that operate on web-page source and show a preview of the resultant web page. Source can be HTML or markup to be translated into HTML.

- WYSIWYM semantic web-page editors. Examples of this type of editor are WYMEditor, RDFaCE, BlueprintUI, PageDown, and Showdown. (The author needs to further investigate these editors.) Source can be HTML or markup that can be translated into HTML.

- online web development tools for testing and debugging code (e.g. JSFiddle.net, CodePen.io, jsbin.com, etc.),

- web-developer's tools and "augmented-browsing software"9, 10 (e.g. Firebug for Firefox, Developer Tools for Chrome, Developer Tools for Safari, Greasemonkey, Tampermonkey, Chickenfoot, X-Ray Goggles, etc.),

- integrated development environments (IDEs) that build websites,

- web content management systems (web CMSs or simply WCMSs),

- website builders,

- web frameworks, and

- web portals.

Contents

- Introduction

- Critique of current WYSIWYG web-page composers

- Critique of current WYSIWYM web-page composers

- Values

- Principles

- Practices

- Initial Questions and Ideas for Zen Development

- Diving Deeper: Zen According to The Elements of User Experience

- Encapsulating the Zen Concept in a Domain Name

- For Further Study

- Notes

2. Critique of current WYSIWYG web-page composers

All the well-known WYSIWYG web-page composers, whether standalone or embedded,

treat web-page composition like word-processing—that is, like a layout

or 2-D-drawing problem—rather than as an organizational

(structured, semantic, dynamic-design) problem.

Typically visual web-page composers are designed

merely to provide a gentle approach to HTML editing,

leaving out important aspects like styling based upon semantic meaning;

div and span elements; reactive widgets; and dynamic (AJAX-enabled) web pages.

They often sport a button to switch to an HTML-source view.

Their interfaces are reminiscent of IDEs or RAD tools provided by frameworks

used by web-developer frameworks.

Indeed, WYSIWYG web-page composers are sometimes included in IDEs.

The HTML they produce tends not to be "clean," in the sense that it contains

excess pieces of HTML, and not well-behaved, as explained by Nick Santos.9

The HTML they produce gets dirtier and dirtier as the user makes more and more

changes to the web page.

The main problem with web-page-embedded, JavaScript-based editors

is that the jobs they are tasked with are extremely difficult and not well supported by web browsers.

Piotrek Koszuliński, lead developer of CKEditor, has written

a detailed technical explanation10

of why the key browser feature supporting web-page editing—contentEditable—is

both flawed and indispensable.

Some of his points are:

- It is difficult to force every browser to use

<strong>instead of<b>for the bold command. - It is difficult to force the Enter key to create new paragraphs instead of

<br>or<div>. - Cleaning up pasted code is messy and imperfect.

- As of August, 2015, the selection systems of the Blink and WebKit web browser engines had been broken for eight years.

- APIs and their implementations related to

contentEditable"are incomplete and/or inconsistent and buggy." - Trying to avoid

contentEditableuncovers many large difficulties in correctly handling composition events (which allow multiple keystrokes to form an accented letter, a complex Japanese character, or a letter with a diacritic) without breaking editing on an iPad, the keystrokes for jumping over words, shake-to-undo on the iPhone, spell checking, and screen readers. - Standardizing browser APIs to address all the above issues is an extremely difficult job. </ol> </p>

- supports composition with OpenAjax widgets,

- "allows User Experience Designers (UXD) to perform drag/drop assembly of live UI mockups,"

- includes "deep support for CSS styling (the application includes a full CSS parser/modeler),"

- includes "a mechanism for organizing a UI prototype into a series of 'application states' (aka 'screens' or 'panels') which allows a UI designer to define interactivity without programming," and

- has a code base with "a toolkit-independent architecture that allows for plugging in arbitrary widget libraries and CSS themes."

- The creation of novel, beautiful, well-formatted, semantic HTML and CSS should be dead simple.

- Amateur web authors should be able to create virtually any kind of page structure and style.

- The interface should have a virtually zero learning curve, and zero should really mean zero. Well-known interface metaphors and gestures must be leveraged to the hilt. The "principle of least surprise" should be followed.

- The interface for manipulating and creating semantic and presentation structure should not be cluttered with details that could be hidden until needed; the user should be able to drill down to these details. The interface should present two modes: one mode to hide purely structural details so that semantic details can be addressed, and another mode to hide semantic details so that the look and feel of a web page can be addressed.

- Meta organization, like the creation of themes, templates, or partials, should not be precluded by the structure of Zen's low-level tools. The creation of these should be empowered, if not directly implemented, by the low-level tools.

- It will run in any browser without a download and without installation. (Sometime in the future an attempt might be made to make it work in mobile browsers.)

- It will be a composition environment, a GUI builder.

- It will store its apps as web pages, even new versions of itself.

- It will use only the DOM's interfaces and APIs17, 18 for the composition of web pages and web GUIs by element insertion, manipulation, editing, and deletion— as opposed to drawing objects using SVG or Canvas operations.

- Zen will not provide IDEs, but instead will allow objects in its compositions to be inspected and edited via a Squeak19-like object inspector. Zen will allow its simple programs to be inspected and edited in a normally hidden visual programming environment, using HTML elements like DIV to model nodes in the program's abstract syntax tree (AST).20 Zen will enable these program nodes or blocks to be copied, pasted, and rearranged, just like the normally visible parts of a Zen web page.

- It will enable its users to easily compose sequential programs, that is, programs that can wait for external, asynchronous events such as user input or I/O. This will be accomplished by instantiating true continuations in an interpretter running on top of JavaScript in the web browser. (See below.)

- It will exist as a library that can be loaded into any web page to provide the page with Zen's capabilities, although caution will be required to ensure compatibility.

- It will complement, augment, and interact with existing web-page editors and website builders, not replace them.

- It will allow the Zen-editing of a web page to be locked, leaving intact the form and behavior it built inside the web page.

- Zen will not add more than 1–3 seconds to the TTI (time to interact) for a web page.

- Zen will not follow Lively Kernel's principle of implementing a scene graph.15 Instead, it will honor the CSS2 visual formatting model21 in its modeling of a document in a web browser. Zen will not be able use SVG or Canvas graphics for the creation of objects, except where particular Zen-composed apps borrow the pertinent capabilities from other software systems.

- A Lego-like construction kit, basically for building a Website (or web page) from scratch? Such a construction kit would concentrate upon a tall stack of capabilities based upon a narrow, "opinionated" trunk of foundational technologies. Examples of the foundational technologies could be a CSS framework like Bootstrap or Foundation, a CSS grid system like 960 Grid System, a CSS framework oriented to working with web components, components from customelements.io or webcomponents.org, and widgets from ExtJS or the Dojo Toolkit.

- A tool kit for creating or modifying web pages? Such a tool kit would concentrate upon the broadest possible comprehension of different kinds of web components in the broadest meaning of the term—including JavaScript-based widgets. Such a tool kit could not reasonably be made to comprehend attached JavaScript, but could understand the protocols of JavaScript-based widget libraries to intervene in and interact with the lifecycle of widgets. Such a tool kit could not reasonably comprehend other JavaScript, but could leave that JavaScript untouched. Such a tool kit could not reasonably be able to add useful, arbitrary JavaScript to a web page, but could add a very broad class of visually programmed functions as described later in this white paper.

- Simple copying, cutting, and pasting of text, images, HTML components, and widgets should be possible. It should be possible to save various versions of these copied or cut items in a repertoire of patterns—with or without the text and images, with or without style classes, with or without style overrides. It should be possible to add parameters to the patterns so they can be used to easiy add to the Web. The patterns should be stored in a version control system that makes branching of versions very easy, as Git40 does.

- The Web user should have the ability to create spreadsheets (like Google Sheets41 via simple drag-and-drop. It should be possible to drag and drop whole cells, rows, and tables without even double-clicking and swiping the mouse pointer across words. These spreadsheets should be able to include images.

- A Web CMS that eschews text-based "code" in favor of a direct manipulation interface (DMI).

- A Web CMS that excels in the management of intermeshed or intertwined trees and meshes of data of many types: Document Object Models (DOMs, including shadow DOMs), including at least nodes implementing the HTMLElement, Attr, and Text interfaces; CSS classes; and link trees and meshes. See "DOM Standard",44 published by the WHATWG community.

- A Web CMS (or WCMS) that can nest web components and widgets with no arbitrary limit.

- An easy way to consume and perhaps even interrelate Web schema. (See schema.org.45)

- Users who are only fluent in the most basic Web-application constructs: URLs (or URIs), browsers, windows, links, and maybe simple, clear buttons.

- Users who are fluent in most of the basic, modern user interface patterns used in modern Web applications like those described in the Yahoo Design Pattern Library46, such as Top Navigation, Accordion, Breadcrumbs, Tabs, Navigation Bar, Calendar Picker, Collapse Transition, Expand Transition, Slide Transition, and Drag and Drop.

- Users with enough prior experience and intelligence to quickly adopt new methods of interaction with computers, such as a Windows user who can adapt to an Apple laptop computer, or a user who can learn about dragging and dropping URLs into a web browser or a images from the web browser to the desktop.

- Users who can productively use a complex, specialized Web application such as a Web-page design application, an application for photo manipulation, a paint application, an application for technical analysis of financial data—an application that typically cannot be learned in less than an hour. Some of the barriers to learning such an application more quickly are jargon, densely packed user interface elements, and domain-specific knowledge.

- A bit of reflection and research determined that I need to seek out experts' Web user segmentation. That quickly turned up the topic of "web analytics user segmentation", where there is much good information available for free. However, "levels of Web user ability" is a topic I have not explored much at all. It appears there is some very good guidance in the blog entry "Enabling new types of web user experiences". A key insight in that post is that currently the dominant model of how web apps should be experienced is that they should be "web ports" of iPhone apps. The author of the post believes that is aiming far too low in aspiration. He gives some examples of devices like doorknobs and toasters broadcasting web services over Bluetooth or WiFi. Such ideas, while not directly providing much help to Zen development, provide inspiration for the necessary lateral thinking.

- Organizing the user's own text collections as hypertext in order to manage relationships between various pieces of information, particularly hypertext documents

- Creating a "notebook" or "log"

- Creating a Web app for further personal Web exploration and use

- Creating a website or Web app for creative or commercial use

- Create any kind of webiste by doing the front-end design, the front-end programming, and the backend programming

- Enable a very short and very simple edit-compile-debug-commit-backup-deploy cycle.

- Use continuations and block-oriented visual programming to enable front-end programming in the simple, logical, linear style of programming for a non-event-driven environment, with operating system constructs like "wait".

- Since it is unnatural and sometimes dangerous to edit a live interface, use a run-edit toggle.

- Use visual paradigms and patterns like sliding DIVs, temporary absolute positioning, the web browser's Z axis, parallax, and drag-and-drop.

- "Own the Web"

- "On the same page"

- "Mash the Web"

- "Remix the Web"

- otw.com ("Own the Web")

- ownweb.com

- pweb.com ("Personal Web")

- cweb.com ("Collaborative Web")

- meweb.com

- otsp.com ("On the Same Page")

- zenweb.com

- zweb.com

- owntheweb.com

- myownweb.com

- nowweb.com

- myweb.com (currently selling emoji collections)

- newweb.com (no DNS address)

- osp.com ("On the Same Page", but currently in use to sell fiberoptic products under the brand name OSP)

- youweb.com (redirects to videomeet.pro)

- yourweb.com (redirects to secureserver.net)

- collabweb.com (in use and might be a competitor to Zen)

- me.com (redirects to Apple's icloud.com)

- GGG and the Semantic Web. (Very important. Could be greatly helped by Zen.)

- Lively Kernel.

- Context Oriented Programming.

- ContextJS.

- Morphic.

- Morphic.js (Morphic for JavaScript).

- doCOUNT, related to Morphic.

- Snap! (formerly named BYOB), related to Squeak Smalltalk and Morphic.

- The principle of Lively Kernel that it has no run/edit mode distinction, that is, the whole environment is live all the time: the environment runs, the debugger, and the editor all run at the same time.

- APIs for clipboard operations such as copy, cut and paste in web applications, as described in "Clipboard API and events"47 on w3.org.

- Publications of the Web Platform Working Group at w3.org.

- "Defining Good," Silicon Valley Product Group

- B. Schneiderman's "Visual Information-Seeking Mantra"

- "A Task by Data Type Taxonomy for Information Visualizations,' B. Schneiderman

- "Programming by Manipulation for Layout", Technical Report

- "Programming by example", Wikipedia

- The W3C's "Accessible Rich Internet Applications (WAI-ARIA) 1.0" recommendation

- Jim Boulton, Kalle Everland, Jesper Lycke, 2014, "The Nexus Browser", digital-archaeology.org, retrieved August 22, 2016.

- Allen Cypher, Mira Dontcheva, Tessa Lau, editors,

- Pallab Ghosh, April 30, 2013, "Cern re-creating first web page to revere early ideals", BBC.com, retrieved August 11, 2016.

- Scott Laningham, August 22, 2006, "developerWorks Interviews: Tim Berners-Lee", IBM.com, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- Berners-Lee, Tim, and Mark Fischetti, 1999, Weaving the Web: The original design and ultimate destiny of the World Wide Web by its inventor, HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco.

- "Browser Support", Mozilla Wiki, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Graded Browser Support", YUI3, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "jQuery Mobile 1.4 Browser Support", jquerymobile.com, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Comparison of web browsers", Wikipedia, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Augmented browsing", Wikipedia, retrieved November 26, 2016.

- "List of augmented browsing software", Wikipedia, retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Rick Santos, May 14, 2014, "Why ContentEditable is Terrible—Or: How the Medium Editor Works", Medium Engineering, retrieved September 11, 2016.

- Piotrek Koszuliński, August 13, 2015, "ContentEditable — The Good, the Bad and the Ugly", Medium, retrieved September 21, 2016.

- Dan Dascalescu, September 6, 2016, "Comparison of JavaScript WYSIWYG editors", Github, retrieved September 21, 2016.

- "WYMeditor", Wikipedia, retrieved August 31, 2016.

- David Ungar, abstract entitled "Self and self: whys and wherefores", Stanford.edu, retrieved August 8, 2016.

- David Ungar, September 30, 2009, video entitled "Self and Self: Whys and Wherefores", YouTub.com, retrieved August 8, 2016.

- Dan Ingalls, "The Live Web. Drag 'n drop in the cloud", YouTube.com, retrieved August 11, 2016.

- "Lively Kernel", lively-kernel.org, retrieved August 11, 2016.

- "DOM—Living Standard", WHATWG.org, retrieved August 11, 2016.

- "Document Object Model FAQ", w3c.org, retrieved September 1, 2016.

- "Inspector", Squeak.org, retrieved October 10, 2016.

- "Abstract syntax tree", Wikipedia, retrieved September 1, 2016.

- "Controlling box generation", Section 9.2 of "Cascading Style Sheets Level 2 Revision 1 (CSS 2.1) Specification" W3C Recommendation, retrieved September 1, 2016.

- David Madore, "A page about call/cc", www.madore.org, retrieved September 1, 2016.

- Steve Wittens, "Shadow DOM—SVG, CSS, React and Angular", Hackery, Math & Design, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "web framework - Google Search", Google, retrieved July 28, 2016.

- "Transclusion", Wikipedia, retrieved July 12, 2016.

- "X-Frame-Options", Mozilla Developer Network, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "chrome memory usage - Google Search", Google, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Tabs Outliner - Chrome Web Store", Google, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Content Analysis Web Service", Yahoo! Developer Network, retrieved October 8, 2016.

- "Xmarks company history", Wikipedia, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Wikipedia category: Discontinued Google services", Wikipedia, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "6 Popular Google Products Which No Longer Exist", The Huffington Post, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Xmarks domain blocked in India", Wikipedia, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Data Breach Tracker: All the Major Companies That Have Been Hacked", Time, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "6 Biggest Business Security Risks and How You Can Fight Back", CIO, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Firm That Exposed Breach Of 'Billion Passwords' Quickly Offered $120 Service To Find Out If You're Affected", Forbes, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "How the Pwnedlist Got Pwned", KrebsonSecurity, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Russian Hackers Amass Over a Billion Internet Passwords", The New York Times, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "The Big Data Breaches of 2014", Forbes, retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "Git", git-scm.com, retrieved July 12, 2016.

- "Google Sheets - create and edit spreadsheets online, for free", Google, retrieved July 12, 2016.

- Jesse James Garrett, October 21, 2002, The Elements of User Experience: User-Centered Design for the Web, New Riders Publishing, New York.

- Jesse James Garrett, "The Elements of User Experience", jjg.net, retrieved September 1, 2016.

- "DOM Standard", WHATWG.org, retrieved October 10, 2016.

- "Home - schema.org", schema.org, retrieved October 10, 2016.

- "Yahoo Design Pattern Library", developer.yahoo.com, retrieved September 1, 2016.

- "Clipboard API and events", w3.org, retrieved September 1, 2016.

Nick Santos explains how HTML is not well behaved in WYSIWYG editors.

For example, he says, all the forms:

<strong><em>Baggins</em></strong>

should be treated the same by the WYSIWYG editor.

An edit to any of these forms should be treated the same,

but, as he says, "For many ContentEditable implementations on the web,

some invisible character or empty span tag may slip into the HTML,

so that two ContentEditable elements behave totally differently (even though they look the same)."

<em><strong>Baggins</strong></em>

<em><strong>Bagg</strong><strong>ins</strong></em>

<em><strong>Bagg</strong></em><strong><em>ins</em></strong>

According to Dan Dascalescu,11 in a survey of about 60 in-browser, WYSIWYG editors, only one editor could paste images directly from the clipboard.

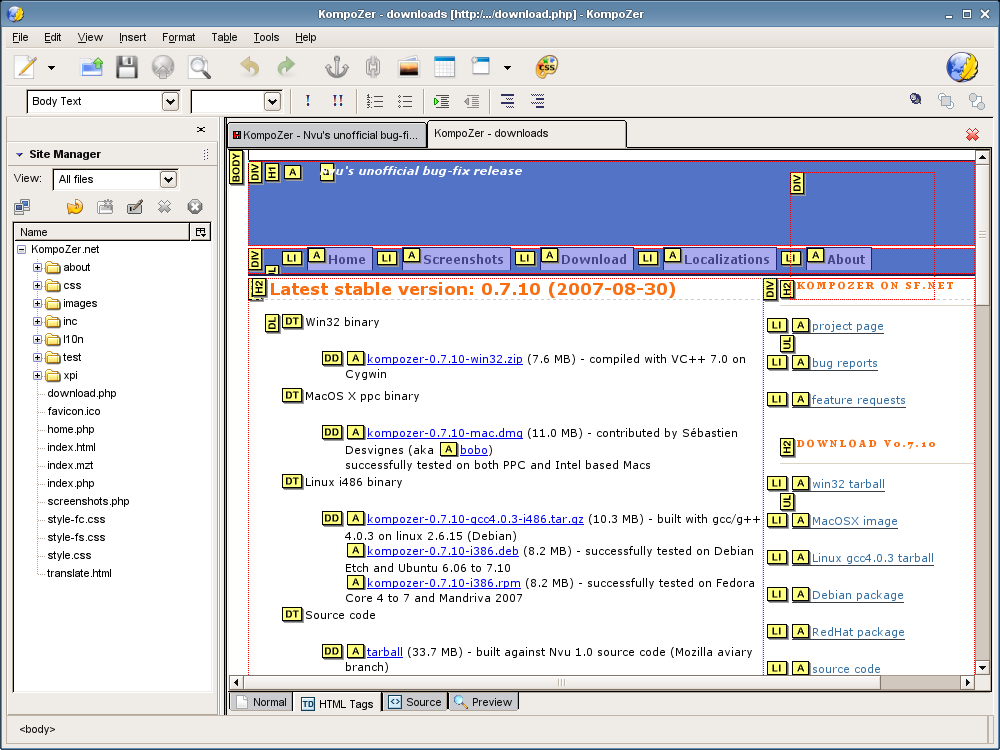

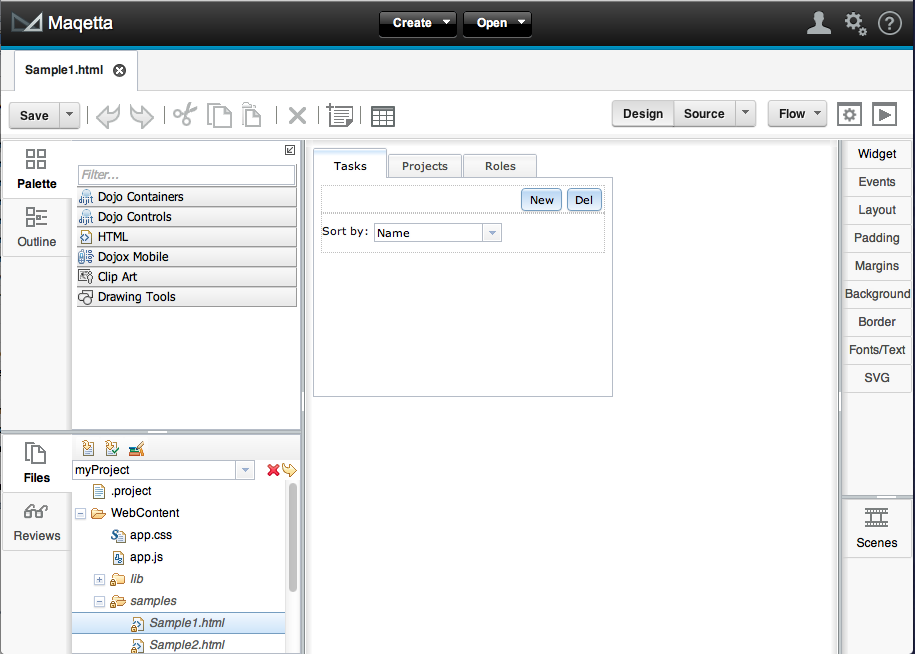

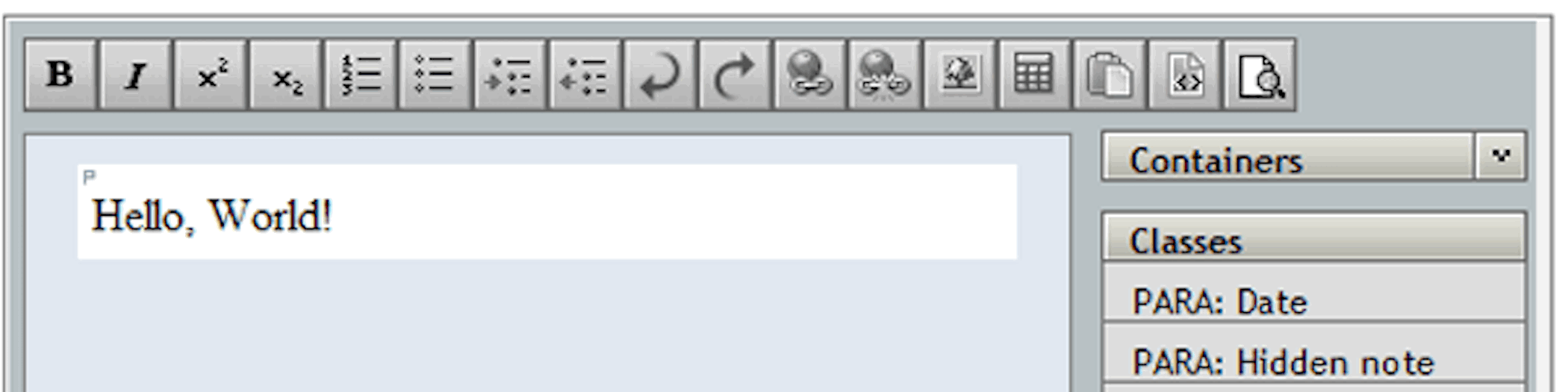

Here are screenshots of a few of the many composers in this class, leaving aside the composers tied to heavyweight integrated development environments:

Aside

Maqetta, although its development is inactive, provides an interesting and unique approach to WYSIWYG web-page composition, in that it3. Critique of current WYSIWYM web-page composers

[This section is to be expanded to cover a representative set of WYSIWYM composers.]

WYMeditor is the best-known WYSIWYM web-page composer.

4. Values

The values driving Zen's development are:

5. Principles

As pointed out by David Ungar (who pioneered the type of prototypal object system that JavaScript uses), from values arise principles and from principles arise practices.13, 14 We have just explored the values behind the Zen system. Now let's explore the principles of the Zen system. Zen will complement the approach of Lively Kernel,15, 16 which shares Zen's principles 1–3 as listed below. How much, if any, of Lively Kernel's code it will borrow is yet to be determined. Note, in particular, the following principle 11 of Zen that is different than the principles of Lively Kernel:

6. Practices

Zen vs. current WYSIWYG and WYSIWYM web-page composers

We have explored the values and principles behind the creation of the Zen system. Now let's explore some of the practices to be followed in Zen's creation.

Present-day WYSIWYG and WYSIWYM web-page composers immediately confront the user with web-page structure details, requiring the user to prematurely optimize his web page. With these composers, the web-page under construction is dominated by a pallette of HTML elements with which the user can "paint" a web page. Some of these composers offer the user a view of the web page that is strewn with icons representing HTML elements.

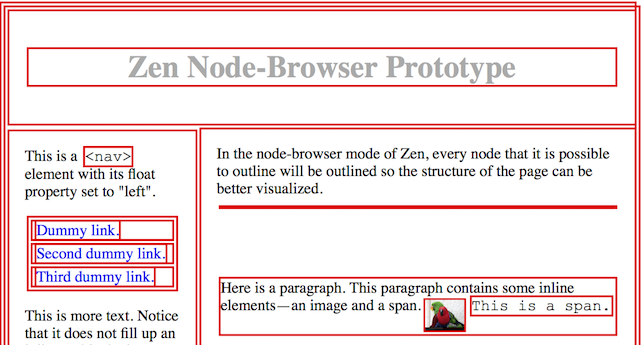

Zen will take a different approach. In Zen, HTML elements making up the web page will represent themselves at the top-level view, with all the obscurity of detail that implies, but when Zen's node browser is open, Zen will be show a view of the web page with all borders and margins styled in such a way that, to the extent possible, all block boxes, inline boxes, and inline-block boxes21 are visible (Figure 7).

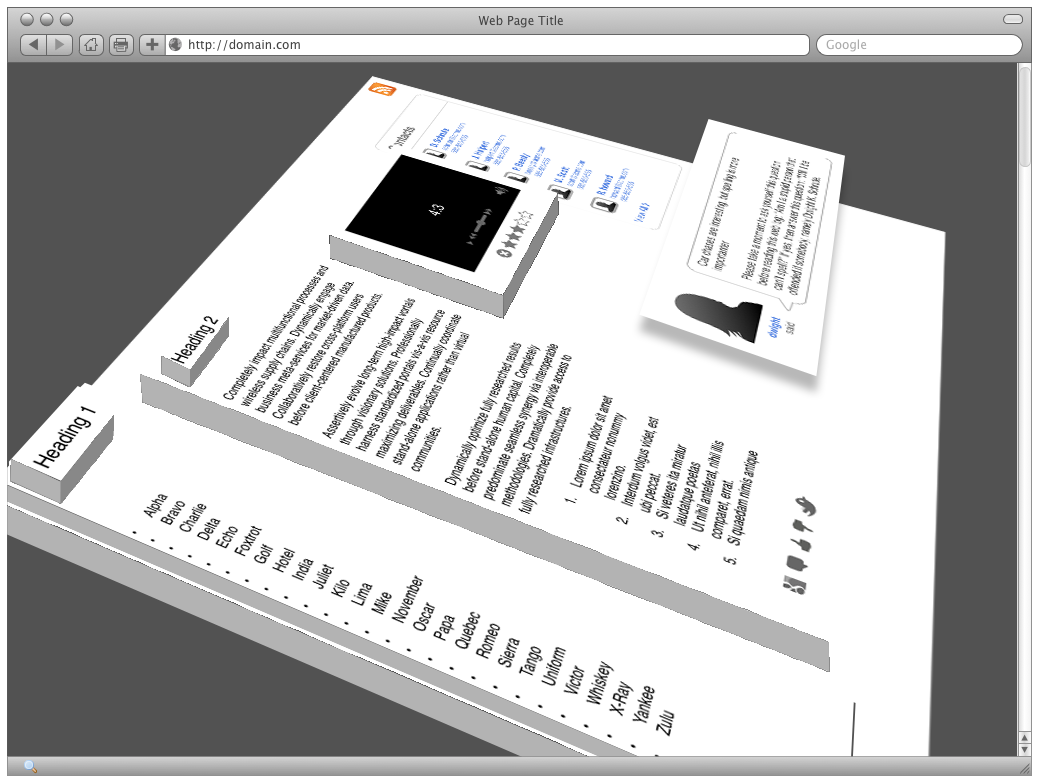

(Other display styles besides block, inline, and inline-block will be modeled by Zen in a subsequent release.) Zen will provide whatever kinds of object-browsers are necessary to unobscure details of the page-as-an-object. Although the details have not yet been worked out, hope and inspiration are provided by the 3D View tool, and by the Tilt 3D add-on, for the Firefox browser (Figure 8).

The user will be able to select any node that can be the target of a mouse event. In node-selection mode, passing the mouse pointer over nodes will highlight them one at a time (Figure 9).

When the user wants to add an HTML element to his web page,

Zen will first present a choice of block, inline, and inline-block box types,

because in Zen's paradighm, the visual behavior of a box is mainly determined

by its display sytle, not by HTML tag type.

This is demonstrated by the w3schools.com's

"Tryit Editor" page for converting <li> HTML elements into a

horizontal

navigation bar.

Using Zen's paradigm, with virtually zero learning, the user could intuitively mock up a web page

using only block, inline, and inline-block boxes,

and convert it piece by piece into semantic markup.

Or he could set the HTML element tag of each element immediately when adding

it to the web page.

Zen will allow the user to inspect and manipulate these boxes in a way pioneered and developed by Smalltalk and Smalltalk variants, using inspectors and browsers to inspect live web-page objects. For a relatively gentle introduction to Smalltalk-style inspectors and browsers, see Cincom Smalltalk's tutorials (Figures 10 and 11). The specific HTML tag of an HTML element will be a detail to be drilled down to rather than a primary detail of interest.

Zen will take an embedded, instant-feedback, hybrid WYSIWYM-WYSIWYG (not "pure" WYSIWYG) approach to pull the authoring of novel, Semantic-Web applications out of the exclusive province of programmer-specialists and put it into the hands of amateurs and dilettantes (in the original, non-pejorative sense of the words). The Zen project will primarily focus upon working with the "purest" web technologies—HTML and CSS—rather than backend technologies like web servers and web frameworks, because the back-end web framework or web server is opaque to JavaScript running in the web page. That is, the JavaScript running in the page has no way to affect the operation of the back end unless specific arrangements have been made for it. Zen will work by providing updates to web-page source in some format. Where web-page source is persisted and how it is used to generate the web page Zen is embedded in will not be the concern of Zen, though a reference implementation for that will be developed along with Zen.

In spite of these strict limitations, Zen as a building block for web servers and web frameworks is anticipated to be a game-changing addition to present-day website and web-app techniques. In some cases, Zen might even be developed to itself reflect changes to content, structure, and style back to sources, using a bit of code on the back end (i.e. on the web server). Perhaps, for example, in WebDAV-enabled websites—Zen could relatively easily be leveraged to rewrite web-page source, including stylesheets. On the other hand, using Zen only as a low-level, embedded, solid building block, it should be possible to augment web frameworks of many types to achieve a new, higher level of interactivity and customization in web applications.

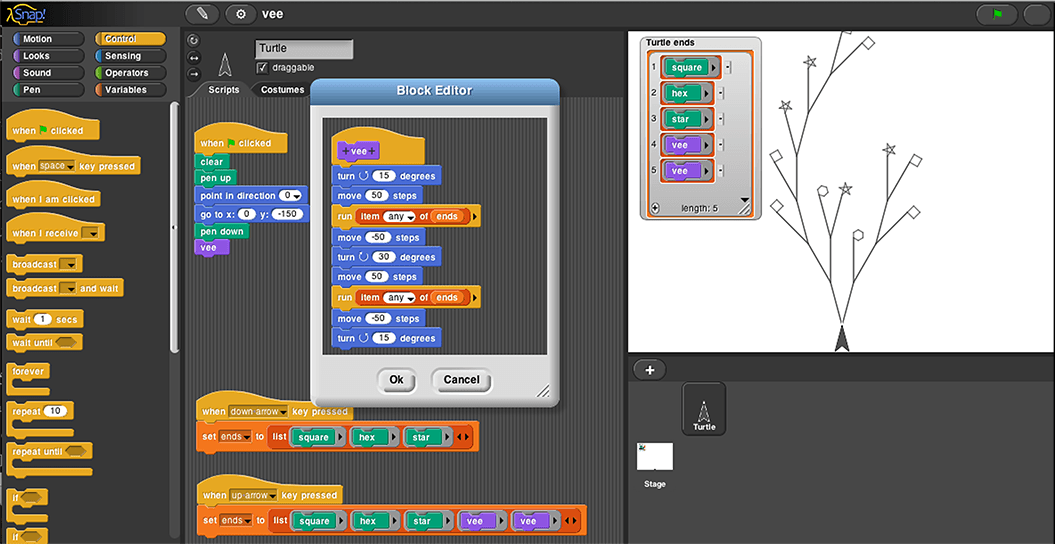

None of the well-known WYSIWYG and WYSIWYM page editors directly support the creation of web applications. The most radical aspect of Zen will be that it will allow simple, sequential programs to be created and edited using a block representation of the program's abstract syntax tree (AST),20 where blocks can be moved around using the same user interface Zen will provide for moving web page elements, with minimal modifications. Zen will accomplish this unusual feat by implementing a version of Scheme language in JavaScript, along with true continuations,22 various supporting functions written in JavaScript, and some resources like icons. The author has already used such continuations to string together JavaScript event handlers to create a small sequential program without resorting to callbacks, continuatinon-passing style, promises, or state machines. Scratch and Snap! (formerly called BYOB) [citations to be added] demonstrate that even young children can program using a cleverly designed visual programming language (Figure 12).

Zen vs. Website Builders

It is important to characterize and visualize how Zen will be different from "website builders" and WCMSs like Wix.com and Weebly.com. In contrast to such WCMSs, which prescribe construction methods at the level of business type, templates, plugins, modules, fonts, etc., Zen will give the user ultimate control of detail at the element/node/NodeList level of web pages. Zen will allow a DOM node to be grabbed and "dragged" to different positions in its containing NodeList because this is the simplest metaphor for that operation. Drag-and-drop is a classic feature of direct-manipulation interfaces (DMIs) and this metaphor of "moving" an HTML element or node is so compelling that we have to look at the code to see that the element has not moved in terms of x and y coordianates, but rather in terms of its cardinal position in a NodeList. Zen will allow a DOM node to be "cut and pasted" to any valid position in the DOM—an interaction between multiple NodeLists. An HTML element's style has four possible, well-supported values for its display property: block, inline, inline-block, and none. Live demo code to implement GUIs to rearrange element positions in the NodeLists of the first three of these display styles is located on the author's GitHub Pages here, here, and here. (Right-click on the links to open the pages in new tabs or windows.) The method of sliding elements in these prototype GUIs was partly inspired by the 15 Puzzle and JavaScript-based implementations of the 15 Puzzle. There are notes about some of these implementations on this website. Below is a screen capture of Jamie Wong's AI-based automated 15-Puzzle solver, which is written solely in JavaScript, HTML, and CSS (Figure 13).

Presently, the customization of templates, plugins, and modules for website builders and web CMSs and the creation of novel comment systems, forums, wikis, and presently unimagined communication systems are far outside the bounds of casual web authorship.

Concessions to Usability

Some concessions to manipulability are necessary so that Zen can successfully edit all webpages. When HTML elements are grabbed Zen should temporarily apply suitable styles to HTML elements like high-contrast borders to make them visible during element selection. When the display-style property of an HTML element is none, Zen should make it possible for users to temporarily set it to another value so the element can be seen. Likewise, wherever desired, Zen should employ similar tactics to make all elements visible and manipulable, whether they are too small; too big; too transparent; or animated. Zen should employ intuitive, adaptive, custom cursors with contrast and distinctive patterns that show up with whatever colors are behind them. The animations in Figures 14 and 15 are actual screen recordings of rough-prototype GUIs for rearranging NodeLists that contain just blocks or just inlines, respectively:

Scope of the Issues Zen Will Address

[This section needs a complete overhaul. Possibly the spectrum analogy should be taken out.]

We must determine the scope of the issues Zen will address, which appears to be huge. Zen is meant to offer a uniquely democratizing way of creating web experiences by avoiding code and instead allowing a Zen user a way to directly manipulate every parameter of his web page to which a metaphor can be applied: block elements can be resized by grabbing their edges; block, inline, and inline-block elements can be grabbed and rearranged; etc. Every time the user changes an aspect of style via Zen, Zen will optionally apply the change to the memory-resident stylesheet holding the previous value of that style or to a new memory-resident stylesheet specific to the element selected for the style. Other options, such as applying the change to a selector chosen or created by Zen, will be offered (to be determined).

This approach is unique in its direct change at the canvas level and in its propagation of changes backward to page source. (See, however, Hybrid HTML/DOM Editors.) Nowdays the creation of web experiences is managed by a galaxy of software packages and services, JavaScript libraries, and CSS libraries, but by viewing this galaxy through the prism of the question "What level of detail does the package or service address," each package and service can be tentatively placed somewhere along a spectrum. [An image is to be included here.] At one end of the spectrum, users or developers deal directly with HTML, CSS, and images, crafting the details of web pages individually, with no further abstraction or intermediation. At the other end of the spectrum, users or developers have at their disposal many abstractions and are coaxed or prodded into dealing with higher-level concerns like minimization of web assets, quick development, responsive design, patterns, standards, metaphors, and affordances. There are problems with this oversimplification, of course, and some packages and services should appear more as a blob rather than as a single point on the spectrum, but the metaphor of a spectrum enables us to filter an unmanageably long list of web technologies so we can concentrate on comparing like with like. Towards one end of the spectrum (the brass-tacks end) is an enormous set of front-end (JavaScript and CSS libraries and toolkits) and back-end (web servers with CGI capabilities), purely for hand-coded website creation, serving, and management, including the management of website-triggered ancilary services like email and payments. Let us call this the "Red End" of the web software and services spectrum. It allows the web developer complete control of his website at the expense of getting his hands very dirty. Right at the Red End, he directly controls every character of his every web page and, if applicable, every table and query definition in his back-end database. A developer working slightly removed from the extreme Red End probably engages with templates, themes, and skins. He might also use plugins. Anywhere close to the Red End or right at the Red End, the developer might use a content management system (CMS) or blog software to create a database-driven dynamic website or a static website (such as Moveable Type used to generate).

The Red End originally comprised just text editors, web servers, and web browsers and was designed and built to use a stateless protocol for transporting hypertext documents. The web was later retrofitted with mobile scripting languages Java and JavaScript to create a platform for distributed applications. Web servers eventually developed sufficiently to support collaborative authoring applications. One cycle of development was thus completed, bringing the web back around to Berner-Lee's original dream of collaborative authoring, but Berners-Lee's original vision of a simple, easy, collaborative authoring tool for everyone lost out to the current ad hoc23 proliferation of non-standard, anonymous, front-end tools.24 These anonymous tools typically do not offer web-technology dilettantes and web power-users the facility to add nested structure to HTML; to add JavaScript-backed widgets like AngularJS, Dojo, ExtJS, jQuery UI, or web-component widgets; to add web forms; to develop CSS class hierarchies and frameworks; or even to collaborate in a structured way. The Red End for nontechnical people can usually only create flat, static layouts of single pages, not complicated, dynamic structures, and it often emphasizes a code view of web pages (raw HTML and CSS) as much as a WYSIWYG view of pages. Thus the Red End for nontechnical people is not very powerful and often is hard to use. Meanwhile, on the back end, control of the web frameworks is mostly left up to programmer-specialists.

Nowdays many web applications are built inside walled gardens. Even IDEs like Eclipse, IntelliJ IDEA, NetBeans are in at least a small sense walled gardens because they impose their own formatting upon source-code files. Many amateur and professional developers do web development using rigid software web application servers that sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars, such as IBM WebSphere Application Server and Red Hat JBoss. Developers who use such application servers often deal with rigidly defined software modules rather than more basic APIs like RDBMS queries and JavaScript library APIs. Nowdays most online collaboration by nontechnical people does not involve the restructuring of web pages or websites. Instead, it only involves the insertion of data, such as blog or forum posts, into databases, to be queried later. This is a very strict limitation. Let us call web application servers and web services the "Violet End" of the web-development level-of-detail spectrum. It is imminently possible to imagine highly flexible, desktop-app-inspired table, form, query, and report design being built into the Violet End, but such capabilities are not common. Nontechnical people are offered very few simple ways to program websites. The latest and greatest "web experience management" software and services promise to bundle all that is needed to handle ... [to be filled in later]. Given the vastness of the field and the inconceivability of a way to integrate all such facilities, they end up with only the appeal of preserved and prepackaged frozen meals. Furthermore, although there are hundreds or thousands of useful web services that can be tapped, very often for free, specialist programming is necessary to use them.

There are many difficulties or problems in implementing simple ideas on the Web due to complexities at the Red End and the leaky abstractions at the Violet End. First we shall list just a few of those problems—not in a very systematic way, but almost like a small collection of anecdotes. After creating an initial small list of problems, we shall take an initial, inadequate stab at listing a set of "solutions". After this first, inadequate attempt, we shall delineate the method we are adopting to conquer them with a set of technologies I have loosely been calling "Zen". Finally, we shall attempt to discover a systematic way of cataloging problems with the Web experience so that functional specifications can be created for software layers and modules to improve the Web experience systematically.

Problem #1: Paucity of means for nontechnical people to author Web documents and websites. One of the biggest problems or shortcomings of current web browsers is their lack of authoring facilities.

Problem #2: No utility for Web copy/cut/paste/mashup. To effectively manage the tremendous load of linked information raining down on him, the Web user should have a robust utility for managing hypermedia in the native environment in which he encounters that hypermedia—the Web environment. A utility built upon the Web can have features that a desktop utility cannot have, foremost of which are instantaneous change and ubiquitous access. The Web user should have high-quality, proven Web user interface shortcuts most appropriate to manipulating information from the Web—for example, the "Rich Interaction" patterns described in the Yahoo Design Pattern Library—so he can quickly clip, mash together, and rearrange information from the Web. This interface must interwork with any A-grade web browser. Incomplete, specialized, "opinionated" services, such as EverNote and Instapaper, do not support the ad hoc creation of drawers, panels, and dialogs, which are necessary to cut, paste, transclude25, organize, associate, link, tag, and hide blocks of information. This problem is inherently related to Problem #1, but it is also related to various Web standards, such as the X-Frame-Options standard.26

Problem #3: Limits to the ability to remember paths through the hypermedia sphere. In 2016, decades after the invention of virtual memory, web browsers still can't get enough memory, causing themselves and their host operating systems to malfunction, to crash, or to function poorly. Never mind the waste of the Web user's time. When the "too many tabs" problem forces the user to close tabs, or causes the browser to slow to a crawl, or crashes the browser, the reminders to the user about how he discovered the Web pages he visited get lost. This is a travesty because many of the user's research insights are won by a hard, painful, lengthy search.27 For now, the problem can only be somewhat ameliorated by adopting rare, non-free tools, such as the Tabs Outliner plugin for the Chrome web browser.28 The right juxtaposition, encapsulation, and highlighting of blocks of information would make it unnecessary to keep open many browser tabs at once and would make it possible to record the user's path through the hypermedia sphere. To make these kinds of arrangement easy, a new utility is necessary.

Problem #4: Bookmark managers inbuilt to web browsers are inadequate for their main purpose. They are too slow to respond to user input. Furthermore, they do not have even the most basic, useful organizational utilities— for example, an interface, such as the desktop's drag-and-drop interface for folders and files, or automatic Web-page-content indexing and retrieval based upon content. Many web services that analyze websites could be proxied automatically by the Web browser: services such as Alexa.com (formerly providing free information), the WHOIS service, and Yahoo's free web service that provides semantic analysis of a website and provides a description of that website.29 Inbuilt bookmark managers are tied to a particular web browser, which forces dependency upon the user—not a good thing.

Problem #5: Lack of personal ownership of bookmarks. Web services such as Xmarks, which archive a user's bookmarks, force the user to give up ultimate responsibility for his own bookmarks and put the bookmarks into the hands of a company or organisation that could go out of existence or suspend services.30, 31, 32 Xmarks was even made unavailable for awhile in India by court order.33 In the last few years there has been panic34, 35 and uncertainty36, 37 surrounding the spate of security breaches by web services that have revealed clients' sensitive data, such as usernames, passwords, and credit-card credentials.38, 39 There should be a utility to make a Web user's bookmarks available offline and/or on the user's own website.

Problem #6: There is no universally available bookmark file facility. Online collaboration is not supported by good integration of bookmark files with the OS desktop. For example, on a Mac, dragging a URL from Safari's address bar to the desktop creates a file with type "webloc" that MS Windows does not understand by default. It is possible to create a file with type "url" that Windows, Mac, and Ubuntu all understand, but this is not currently happening.

7. Initial Questions and Ideas for Zen Development

Now we shall make our first foray into describing Zen. How do we propose to solve the problems listed in "Introduction"? Which of the following do we want to focus upon?

Whichever path we choose—the creation of an isolated silo of technology or the utility belt of tools—there are some data-wrangling capabilities it seems Web users should be getting for free, but aren't. These could be part of a Zen Manifesto:

8. Diving Deeper: Zen According to The Elements of User Experience

Jesse James Garrett, who coined the term AJAX, wrote an influential book entitled The Elements of User Experience42, which will serve to inform the strategy for the development of Zen. (The acronym AJAX refers to a set of Web technologies that enable the Web to be used as a remote software interface and employing JavaScript and asynchronous HTTP requests.) Garrett's elements are summarized in a chart43. The "Surface Plane" described in that book corresponds roughly to the concerns of the Red End; the "Strategy Plane" to the concerns of the Violet End.

User Needs for a "Zen Website"

There is a very specific set of user needs that a "Zen website" could uniquely fulfil. At least some of these are:

Site Objectives of a "Zen Website"

If there is a site objective, then there must be a website. If that website has a tight focus, it must be oriented toward a particular segment of its entire potential user population (that is, anyone who comes to the website). My initial attempt to segment users was this:

Some Zen website use cases could be:

9. Encapsulating the Zen Concept in a Domain Name

How to convey the proper central concept behind the "Zen website"? Is the central concept for the Zen website all about being "on the same page"? Would a better encapsulation of the gestalt of Zen be "own the web" or "your web" or "my web" or "mash the web"? Possible catch phrases to encapsulate the gestalt of Zen are:

me could convey the personalization aspect of Zen.